The rate also influences short-term interest rates, albeit indirectly, for everything from home and auto loans to credit cards, as lenders often set their rates based on the prime lending rate. The prime rate is the rate banks charge their most creditworthy borrowers and is influenced by the federal funds rate, as well. For monetary policy purposes, the Federal Reserve sets a target for the federal funds rate and maintains that target interest rate by buying and selling U.S. When the Fed buys securities, bank reserves rise, and the fed funds rate tends to fall. When the Fed sells securities, bank reserves fall, and the fed funds rate tends to rise.

European Central Bank set for a rate cut in September, economists predict

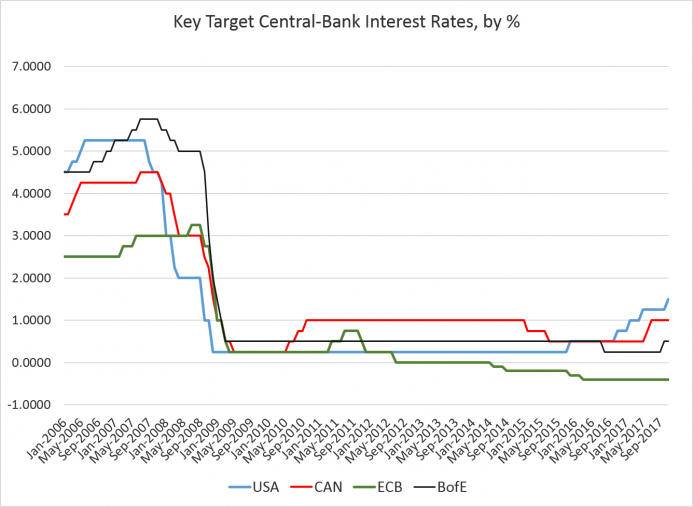

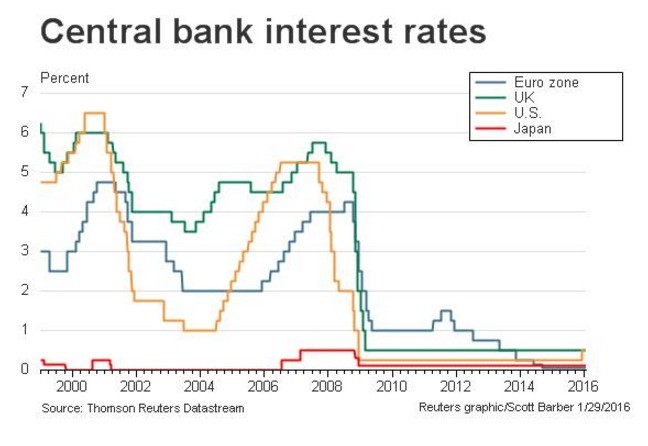

The Board decides on changes in discount rates after recommendations submitted by one or more of the regional Federal Reserve Banks. The FOMC decides on open market operations, including the desired levels of central bank money or the desired federal funds market rate. The federal funds target rate is set by the governors of the Federal Reserve, which they enforce by open market operations and adjustments in the interest rate on reserves. The last full cycle of rate increases occurred between June 2004 and June 2006 as rates steadily rose from 1.00% to 5.25%. The target rate remained at 5.25% for over a year, until the Federal Reserve began lowering rates in September 2007.

In the United States, the federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions (banks and credit unions) lend reserve balances to other depository institutions overnight on an uncollateralized basis. Reserve balances are amounts held at the Federal Reserve to maintain depository institutions’ reserve requirements. Institutions with surplus balances in their accounts lend those balances to institutions in need of larger balances.

Buying and selling securities, or open market operations, is the Fed’s primary tool for implementing monetary policy. Since January 2003, when the Federal Reserve System implemented a “penalty” discount rate policy, the discount rate has been about 1 percentage point, or 100 basis points, above the effective (market) federal funds rate.

Market expectations about those short-term rates, combined with other factors, affect the longer-term rates that are applied to business investment loans and consumer borrowing for mortgages or car loans. Open market operations (OMOs)–the purchase and sale of securities in the open market by a central bank–are a key tool used by the Federal Reserve in the implementation of monetary policy. The short-term objective for open market operations is specified by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the monetary policy-making body of the Federal Reserve System, meets eight times a year to set the federal funds rate.

The Federal Reserve uses monetary policy to achieve its statutory mandate, which is to foster maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. Setting the target for the federal funds rate is therefore an important tool for the bank because that rate is the benchmark for Treasury bills and other short-term interest rates.

While the FOMC can’t mandate a particular federal funds rate, the Federal Reserve System can adjust the money supply so that interest rates will move toward the target rate. By increasing the amount of money in the system it can cause interest rates to fall. Conversely, by decreasing the money supply it can make interest rates rise.

The FOMC makes its decisions about rate adjustments based on key economic indicators that may show signs of inflation, recession, or other issues that can affect sustainable economic growth. The Federal Reserve’s approach to the implementation of monetary policy has evolved considerably since the financial crisis, and particularly so since late 2008 when the FOMC established a near-zero target range for the federal funds rate. The federal funds rate is one of the most important interest rates in the U.S. economy since it affects monetary and financial conditions, which in turn have a bearing on critical aspects of the broader economy including employment, growth, and inflation.

- The Federal Reserve uses monetary policy to achieve its statutory mandate, which is to foster maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.

Another way banks can borrow funds to keep up their required reserves is by taking a loan from the Federal Reserve itself at the discount window. These loans are subject to audit by the Fed, and the discount rate is usually higher than the federal funds rate.

How the Fed Funds Rate Works

For instance, in the Janet Yellen era, the target rate for the federal funds rate was tied to 2% annual inflation. A change in the federal funds rate can affect other short-term interest rates, longer-term interest rates, foreign exchange rates, stock prices, the amount of money and credit in the economy, employment and the prices of goods and services. For 7 years after the financial crisis that began in 2008, the Federal Reserve held the federal funds rate close to zero to help the economy recover. It began increasing that target rate in December 2015; there were eight subsequent increases — the most recent one occurring in December 2018.

The last cycle of easing monetary policy through the rate was conducted from September 2007 to December 2008 as the target rate fell from 5.25% to a range of 0.00–0.25%. Between December 2008 and December 2015 the target rate remained at 0.00–0.25%, the lowest rate in the Federal Reserve’s history, as a reaction to the Financial crisis of 2007–2008 and its aftermath. Considering the wide impact a change in the federal funds rate can have on the value of the dollar and the amount of lending going to new economic activity, the Federal Reserve is closely watched by the market. The prices of Option contracts on fed funds futures (traded on the Chicago Board of Trade) can be used to infer the market’s expectations of future Fed policy changes. One set of such implied probabilities is published by the Cleveland Fed.

The fed funds rate is the interest rate that depository institutions—banks, savings and loans, and credit unions—charge each other for overnight loans. The discount rate is the interest rate that Federal Reserve Banks charge when they make collateralized loans—usually overnight—to depository institutions. In the United States, the authority to set interest rates is divided between the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve (Board) and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

The federal funds rate is an important benchmark in financial markets. The Federal Reserve has responded to a potential slow-down by lowering the target federal funds rate during recessions and other periods of lower growth. In fact, the Committee’s lowering has recently predated recessions, in order to stimulate the economy and cushion the fall. Reducing the federal funds rate makes money cheaper, allowing an influx of credit into the economy through all types of loans.

Confusion between these two kinds of loans often leads to confusion between the federal funds rate and the discount rate. Another difference is that while the Fed cannot set an exact federal funds rate, it does set the specific discount rate.

The Fed lowered its benchmark rate again—this time to almost zero

Raising the federal funds rate will dissuade banks from taking out such inter-bank loans, which in turn will make cash that much harder to procure. Conversely, dropping the interest rates will encourage banks to borrow money and therefore invest more freely. This interest rate is used as a regulatory tool to control how freely the U.S. economy operates.