They can be moved into and out of the plan with relative ease, while ownership remains with those committed to the business. For employees, there’s no need to purchase phantoms stock shares as regular stockholders must do on the open market. Instead, phantom shares are given to employees with no money changing hands. That’s a big benefit to employees, who share in the stock’s profits without having to pay for it.

The chapter closes with suggestions for future research on the nonprofit performing arts. For example, companies must strictly adhere to the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) Tax rule 409A statute. This rule limits a company’s options in instituting distribution dates and also blocks employees and managers from accelerating phantom stock payouts if they deem the company to be in severe financial stress.

You may want to spell out in the phantom-equity agreement that the company has the option of paying the departing employee in cash or in a loan, typically over a three-year period (with interest at prime), to avoid a sudden cash drain. Phantom equity is essentially a deferred compensation agreement between the company and the employee.

This paper takes stock of what we know about the role of nonprofit enterprise in the production and distribution of the arts (broadly defined), primarily in the United States. After briefly discussing measurement, I present data on the extent of nonprofit activity in a range of cultural subfields. I then review theoretical explanations of the prevalence of nonprofits in cultural industries and discuss some puzzles that existing theories do not adequately solve.

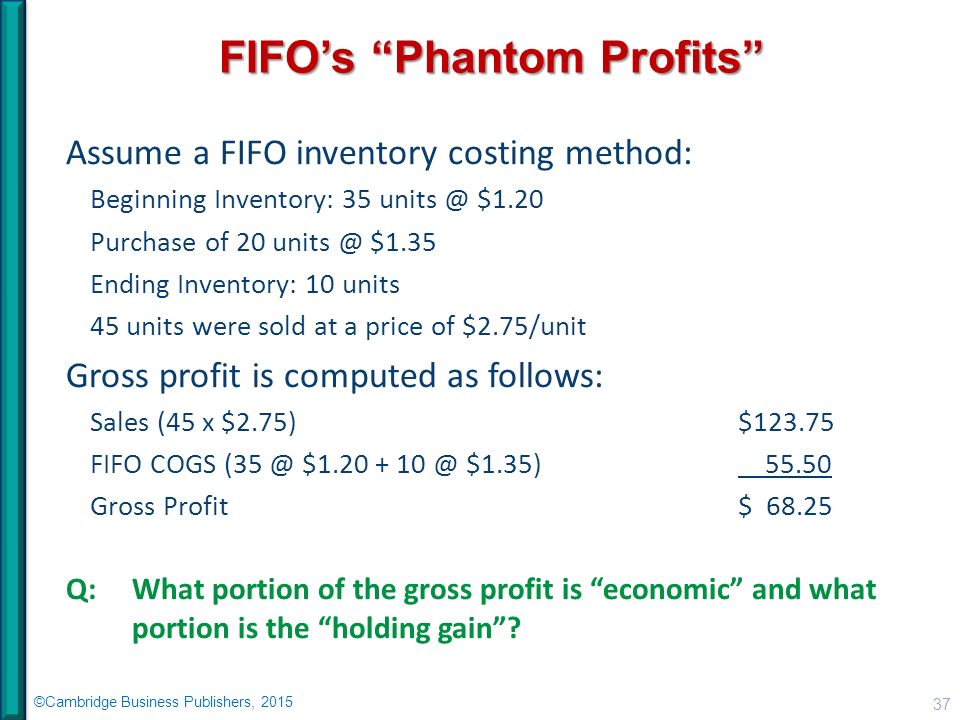

Definition of phantom profit

problems and complications for employees otherwise not looking for ownership. No additional state filings are required for those same employees. There are also no ownership complications if employees come and go.

You can pay bonuses in the form of phantom equity—a boon to fast-growing companies that need all their cash to finance expansion. The phantom shares can be fully vested immediately, or else vest over a period of time—your choice. Just as with an ESOP, employees who receive phantom equity develop a stake, sometimes a sizable one, in the growth and profitability of the company. In that regard, companies use phantom stocks both as a motivational tool to reward employees and to give those employees “skin in the game” to increase workplace productivity and earn the company more profits. This formula drives the company’s stock price higher, as well.

Instead, I argue that nonprofits arise when consumers integrate into production; consumers, supported by institutions, organize to produce a nonrival good for their own consumption, and in so doing are able to achieve first-best. This modeling approach, developed in the context of classical performing arts, may have application in other industries in which nonprofits compete, such as health care, research and development (R&D), and education.

Also, companies can include provisions in a phantom stock agreement that “forfeits” any phantom stock benefits if the employee in question departs the company before the agreed vesting completion date. Phantom stocks are a form of employee compensation that gives employees access to stock ownership without actually owning the stock. Like any genuine stock, phantom stocks rise and fall in value in line with the underlying company stock, and staffers are compensated with profits incurred from any company stock appreciation on specific dates.

- The dominant theory of financial markets, the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), states that in an efficient market the price of a financial asset reflects publicly available information about that asset.

Some companies offer senior employees benefits packages that include phantom stock. With these offerings, the employee receives some of the benefits of owning shares without having actual ownership of company stock. This article applies contract-theory to explain why nonprofits exist and how they compete for profits.

At the end of the vesting period, the company’s stock has risen to $40 per share. Under that scenario, employee “A”—after the five-year period was up. They would receive the difference between the $20 per-share current value of the stock—on the date when the deal was struck—and the $40 share price on the date when they become entitled to any profits from the stock.

Thus, we apply an economic theory of nonprofits to the NYSE to identify the incentives of Exchange members and the various governance mechanisms they created in response. Together, these mechanisms generated what we term “synthetic inertia”, which made prices on the NYSE relatively well-behaved. We hypothesize that NYSE demutualization — converting from nonprofit to for-profit — altered the incentives of the NYSE and undermined this synthetic inertia and thus informational efficiency. We believe that our approach helps resolve an apparent tension between competing theories of market behavior and contributes an analytical framework from which to consider regulatory changes.

For employees, the company calls all the shots in a phantom equity deal, giving them little control or maneuverability if the share price goes south. They also may be terminated before the deal triggers, over issues outside the employee’s control, leaving them out of luck on collecting any phantom stock cash benefits. Company control of phantom stocks is advantageous to employers, as well. Under a typical phantom stock charter or contract, companies can dictate the structure of the agreement. For example, the company can control the level of equity participation in the form of dividends paid out to employees.

I then ask why performing arts nonprofits exist, taking into account the objectives of both consumers and suppliers of performing arts services. Next, I study the production and cost conditions that these firms face, paying particular attention to issues such as product quality, product cross-subsidization, and the so-called “cost disease”. The issue of revenue sources and their generation follows, with a special emphasis on earned revenues, donations, and government subsidies. This discussion includes topics such as ticket pricing strategies, fundraising innovations, and the relationship between private giving and public funding.

Companies as diverse as Publix Supermarkets, Saatchi & Saatchi, and Proctor & Gamble offer—or have offered—employees some form of phantom stock ownership as part of their employee compensation packages. Expect more firms to follow as they realize the possible benefits of implementing phantom stock for employee compensation campaigns. The nonprofit performing arts have received substantial attention in the cultural economics literature, and represent an interesting application for many areas of economic inquiry.

This chapter surveys the relevant theory and the most prominent empirical studies on performing arts nonprofits. The chapter begins with a description of the nonprofit sector – and the role of the performing arts in this sector – around the world.

The dominant theory of financial markets, the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), states that in an efficient market the price of a financial asset reflects publicly available information about that asset. Competing theories, such as behavioral finance, argue that other factors, including irrational investor behavior, impact the price of financial assets. We argue, however, that an analysis of market institutions can help explain when and why the EMH works. Although not widely examined, we argue it is significant that until very recently the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), whose listed companies’ price behavior inspired the EMH, was a nonprofit organization.

Before-tax profit margin

In such cases, partners should consult with tax professionals to ensure that their cash distributions cover their tax burden, that the company pays the taxes on undistributed phantom income or that the burden is spread over a longer period. Second, suppose an employee with vested shares leaves the company. Departing employees will need to be paid cash compensation for the value of their equity.

phantom profits definition

Employees who hold phantom equity do have a claim on the economic value and growth of the company. The value of their phantom shares reflects the value of actual shares. Phantom stock plans can be both a good employee motivation tool for employers and a solid cash incentive plan for employees.

If events go sour and the stock price doesn’t appreciate, neither the employer or employee loses any money directly in the deal. When phantom stocks are awarded, a “delay mechanism” kicks in, where the actual financial payout is made after a long period. However, it depends on the agreement made between the company and the employees.